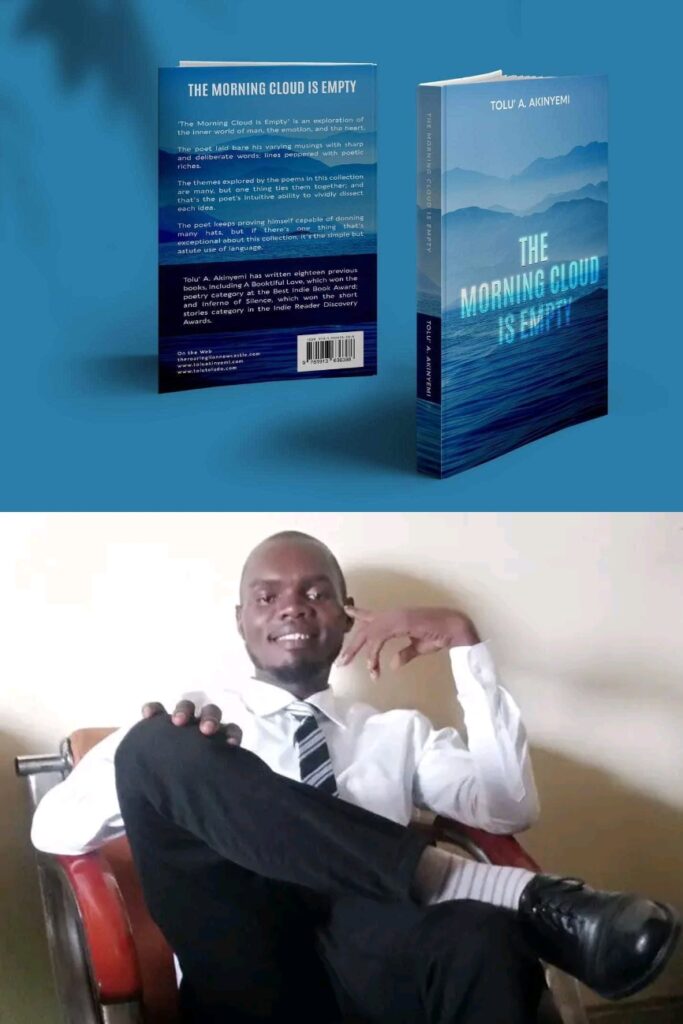

Looking through the Lens of Words into an Empty Morning Cloud: A Review of Tolu’ A. Akinyemi’s The Morning Cloud is Empty

Tolu’ A. Akinyemi, who has published one poetry chapbook and fifteen collections of poems, among which are Dead Lions Don’t Roar, Dead Dogs Don’t Bark, Dead Cats Don’t Meow, A Booktiful Love, City of Lost Memories, Born in Lockdown, etc., has been consistent not only in his thematic leaning on the human condition, but on a peculiar style that converges narrative with language. In The Morning Cloud Is Empty, he retains the same stylistic consciousness which keeps his poetry on the threshold of socio-cultural enlightenment. In this particular collection, Akinyemi writes for the people, rather than his fellow literary scholars. This is evident in his use of common social colloquial which bellies the diction of the poems. More than the simple renderings of the poems, the message is easily heralded, not absorbed by absurd idioms, even so, without distorting their artistic depths. It is one hallmark I find awe-gripping about this book, and the tidal growth of Akinyemi who doubles as a corporate compliance consultant, essayist, storyteller and a writer of children’s books.

In fifty-four poems, Akinyemi navigates the precincts of everyday experiences, writing even the seemingly mundane with compassionate penchant that could endear even the most detached of philistines. One easily spots his purpose in the line from the first poem, “Float”, where he writes: “We could be forerunners” of social change, for one—often than never—realises, from the first page to the last, that Akinyemi writes toward the urgent need for cultural, political, economic, even ideological reformation.

The uncertainties of life/dream, war, hunger, suffering, chaos, disorderliness (that have engulfed postmodern world), gender issues, love, patriotism, betrayal, family, legacy, lineage, etc., are amongst the major themes in this collection. Akinyemi flows from one concern, anxiety, lamentation, heartbreak, hope, love, to the other. The persona in the poems in this collection is restless, for, like a typical artist, trapped in time, reality often pricks his conscience, hence, his pen. In the poem, “Dreams”, he writes: “My dreams are an unfinished novel/with a quantum of characters.” How can the “dream” of an artist ever get “finished” when, daily, he wakes into existential “twists and turns” (“Dreams”), when life itself becomes “slithering erosion;” when the familiar news is: “Omicron arrived on our shores unannounced/like the villain/that comes to plunder a land”? The artist can hardly stop looking, and/or showing through the lens of words.

But what [this kind of] art does with the adversary in its crucible is to remold it into hope, love, holding high the torch of certainty. In The Morning Cloud Is Empty, Akinyemi does not leave the “emptiness” in the world to linger; he casts a bridge of hope, love and certainty on it so that anyone who reads (anyone who looks through the lens of his words) can navigate their way in the cloudy horizon, such as in the admonishing poem, “Guard your Peace”, in which he writes: “I prize my peace above all else/for this calming sea is/the anchor of a stable life.” In “Tender Soul”, he admonishes women thus: “inside you, wash away/the bitterness clinging to your soul”— “bitterness” caused by “the cruelty of the world” which often makes the woman “a steaming soup.”

Although The Morning Cloud Is Empty covers a wide range of themes, it is written without any marked structure, apart from the use of tapering titling where certain words tend to appear in the titles of several poems; words like “pandemic”, which appears in the poems: “Pandemic of Empty Pockets” (I & II), “Pandemic of Greed” (I & II), “Pandemic of Empty Stomach.” There’s also the recursive use of the word “hill” in the titles of several poems, like: “Hill of Hope”, “Hill of Broken Dreams”, “Hill of Life and Death.” Then, there’s the repetitive use of the eponymous title, “The Morning Cloud Is Empty”, only differentiated by numerals (I, II and III), as titles of the poems on pages: 3, 28 and 39. Two things seem implicit in this manner of structuring: first, the organic thematic focus of the collection; second, the dearth of artistry, a lack of recourse to the significance of style in literary work. This shortcoming is even made more poignant by the associative meaning encountered in all the words in each of the poems in which they appear.

While the necessity of ‘associative meaning’ is only but predictable by virtue of organic thematic chain that runs through the poems, the proliferation of such in the collection also hints at the dearth of literary adornment, the poet’s lack of recourse to form as a requisite to delivering content. In this collection, it seems, Akinyemi is concerned with content at the peril of form. Apart from titling, observed above, this shortcoming is reflected in the cliché expressions in some of the poems, such as: “I am not one to fall for such cock-and-bull stories” (“Mammy Water”), “the anti-corruption police are chasing shadows/chasing the innocent/till they ignite a revolution” (“Leaking Vaults”), etc.

However, the poem, “Mammy Water” depicts Akinyemi’s knowledge of myth and African mythology. This is further shown in his display of this knowledge (of African mythology) about his ancestry, and the myth of naming in African culture and tradition in the trilogy poems, “My Name” (I, II and III). In these poems, Akinyemi reveals that in African culture and tradition, names are not just ascribed to children without a deep, underlying meaning, significant to either familial or communal history or belief system; names mark significant events or belief system peculiar to where a child is from. Names mean so much to Africans, as they are markers of heritage, the history of one’s origin and ancestry. It symbolises identity, as he writes in “My Name I”—“my name is an incantation/in my grandmother’s mouth.” In “My Name III”, he writes: “my forebearers are hardworking farmers/who stand tall to peel harvested yams/my name is a badge of resilience.”

Akinyemi may be writing about a “morning cloud” that is “empty”, but beyond this cloud, there are stars of hope, glorification, certainty and love glittering. Such is the power of this collection, as it does not end with lamentation/grief over the “emptiness” of the human condition but holds high the torch of words for anyone who looks through to see hope and perseverance. While it is worth recommending that he works on his form in the delivery of his content, he should also be more nuanced in articulating his contents.

Contributor’s Bio

Nket Godwin is a poet, literary critic/essayist and book reviewer. His works have appeared or are forthcoming on Afrocritik, Africanwriter magazine, Konyashamrumi, Lionandlilac magazine, Eboquill, Best Poet of the Year, 2020 Anthology published by Inner Child Press, US, How to Fall in Love Anthology, HaikuNetra magazine, etc. He writes from the city of Port Harcourt, Rivers State. He can be reached via: Twitter (X): @nketgodwin96 Facebook: @Nketgodwin IG: @nketgodwin Email: [email protected]

Wow, such a great work!